Music, by definition, is notes organized in time. The same twelve notes are arranged and stacked in innumerable ways to create what we know as music in the Western world. However, the last couple centuries of listening, performing, and composing have proven music to be much more than a mere collection of sounds. Music transcends its technical definition and offers a deeper emotional connection with its listeners, which we experience in our very own lives. The deeper emotional abilities of music are what ultimately make it matter to us.

Looking back, emotion and music have always been intertwined; we feel melancholy listening to a particularly moving Tchaikovsky piece or feel energized from a blaring AC/DC song. Take Beatles fans from the ’60s, for example. The teenage fans swept away with Beatlemania were screaming and weeping non-stop at their concerts, so much so that even the band couldn’t hear themselves playing. The uncontrollable tears and shrieks of the young fans suggest emotion is an inseparable partner of music.

The ability of music to invoke emotion in a person is what makes it matter to people, rather than it just being “good.” Songs that stir up feelings in someone create a lasting impression, and hence become something that goes beyond a string of notes. A specific source of music’s emotional value can be found in the memories or people associated with the songs. The proposals happening at Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour demonstrate this, as shown by the numerous online videos showcasing couples getting engaged to Taylor’s “You Belong with Me” during her shows. To them, “You Belong with Me” begins to carry a bigger meaning than the song itself: it represents a moment of significant joy and change in their lives. The importance of this song stems not in the musical composition or choice of chords, but in the associated memories shared with a significant other. It does not matter if a song is considered well-written, because it has already transcended itself. In this way, music begins to form a personal relationship with its listener only when some kind of emotion is present.

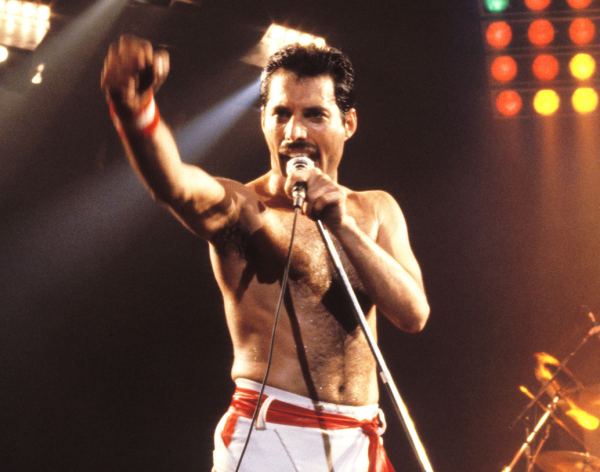

However, music is not restricted to one individual, and is open to connecting with a larger body of people. Music’s universality allows it to speak to billions at once, and unite them into one. In 1985’s Live Aid—a benefit concert fundraising for Ethiopia—Queen’s frontman Freddie Mercury was able to freely conduct Wembley Stadium to repeat his signature vocalizations.

“Aaaaaay-o!” Freddie would sing.

“Aaaaaay-o!” the stadium full of 72,000 people would shout back.

It was a musical exchange between him and the world, in which more than a billion viewers around the globe were united under the same notes. Later, it was coined as “The Note Heard Round the World.” Freddie freely interacting with the crowds was less about what he was singing, but rather about the fact that billions were coming together for a single cause. In other words, the emotional value went beyond the song itself. The unification of the audiences was a direct result from the emotional connection established between them and Queen’s music; because Queen mattered, people were united under one voice.

Music has cemented itself as an art form unlike any other, transcending centuries and empires alike. Despite the popular focus on complexity and musicality as absolute indicators of good and bad music, what really matters are the emotional connections music brings, which inevitably differ from person to person. We fall in love with music because it reminds us of loved ones, empathizes with us, and conjures up feelings never felt before. It ceases to be a collection of notes and instead represents memories and emotions. It is truly a wonder to think that just twelve notes arranged in time are able to embody feelings of hope, reminiscence, heartbreak, and comfort.