Sweet, sour, salty, bitter, umami. These are universally accepted as the five basic tastes that make up our perception of food. But what exactly is behind the sense we call “taste”? The development of taste as we define it today dates back to the age of primates and has evolved over time to correlate certain foods to certain tastes based on the amount of nutrients being provided to nourish our bodies. Essentially, our bodies have developed taste receptors in accordance to which foods suit our specific needs the best.

Before understanding how taste has evolved, we must first establish what makes up the process of tasting and why exactly humans have developed this particular process. Taste must have served a purpose in ensuring our survival; otherwise our body would not have used our limited resources to create taste-specific mechanisms.

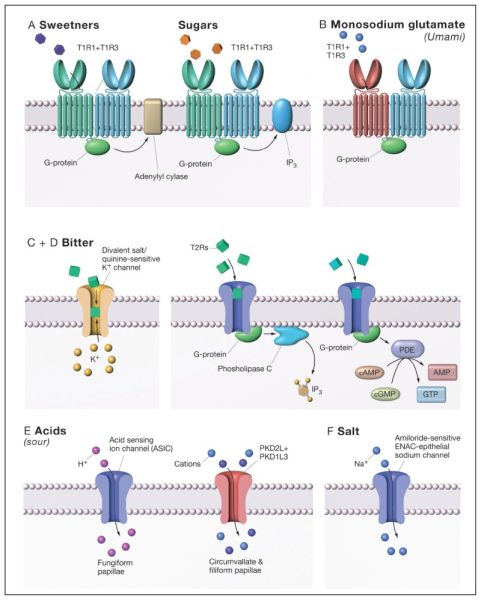

Our gustatory system, or tasting system, perceives flavor using organs known as taste buds; the different types each acting as a receptor to one of the five basic tastes. For instance, one taste bud may be a receptor for sugar molecules, and it detects sweetness. Accordingly, a taste bud that is a receptor for salt molecules detects saltiness. Each species maintains a variety of receptors to taste the different types of food being consumed.

Considering that each of the five taste properties has its own receptor, it only makes sense that each species has evolved an advantageous set of receptors uniquely suited to their nutritional needs. This is the reasoning behind the correlation between the range of an animal’s diet and the complexity of their gustatory systems. To illustrate, koalas that only eat certain leaves have comparatively simple gustatory systems. Their extremely limited diet means that they have little need for extensive taste receptors, and therefore have excluded them from their system. On the other end of the spectrum, extreme carnivores may still have the ability to taste proteins in meat, but also have compromised other taste receptors as shown through how cats lack the ability to taste sweet with their carnivorous diets.

So why have humans retained the ability to taste nearly everything? It must serve some special purpose that aids our survival, or it would have been eliminated through evolution.

The truth is simple: being able to perceive all aspects of taste helps us choose what to eat and what not to eat. Some taste properties, such as sweetness, are intrinsically attractive to us. In contrast, humans tend to reject strong bitterness, as it can be associated with toxins. Still, we can tolerate slight bitterness in foods as it often correlates with micronutrients in plants. The relationship between nutrient-rich foods and positively associated tastes is the foundation of how humans determine which foods are helpful versus harmful.

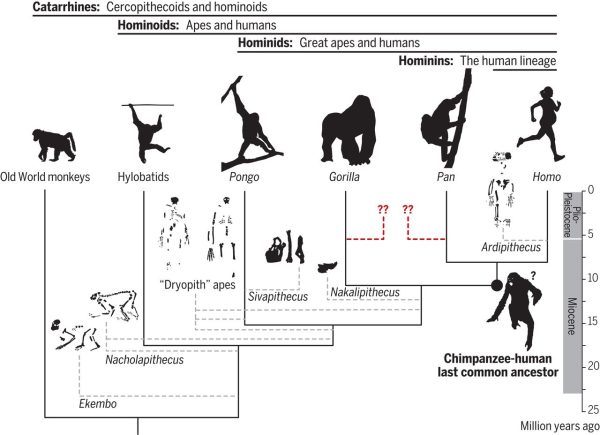

How exactly did humans evolve such preferences for each taste? Our evolutionary ancestors—the primates—and their diets can help us answer that question. Looking back to the original primates evolving into apes, we can see that their diet historically consisted mostly of tropical fruits, leaves, and forest plants. Our attraction to sugar and fruits to this day may have its origins traced to these same ancestors. Branching out from this evolutionary line, modern humans and our closest ancestors fall within the group of hominins, the oldest of which began exploring more open terrain outside the forest. There, they discovered easily digestible proteins in the form of meat—much more convenient than the forest plants that apes used for protein. In addition to small animals, the hominins also hunted elephants, rhinos, and giraffes. They found that umami was a reliable marker of digestible proteins in cooked meats, and developed preferences for molecules that are perceived as umami—hence why we have maintained this preference for umami.

The relationship between one’s diet in conjunction with foods they eat has evolved differently in each species as they develop their own set of taste receptors responsible for determining which foods they should or should not eat. For humans in particular, our preferences for sweet and umami tastes have been shaped by our hominid ancestors who enjoyed a diet of fruits and meats, both providing a nutrient-rich diet advantageous to the species’ survival. Ultimately, it’s extremely fascinating how our perception of what tastes good and bad is less up to us and has more to do with the fascinating biology and evolution of our ancestors.