Loyalties, Litigation, and Lawlessness: How California’s Bullet Train has Ground to a Halt

While the high-speed rail system between San Francisco and Los Angeles was initially touted as a cheap, environmentally safe alternative to current modes of transport, endless litigation and delays have severely undermined this project’s chances of ever reaching completion.

April 30, 2023

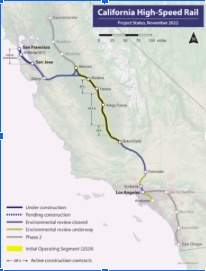

In 2008, California voters narrowly approved plans for a high-speed rail system to be built between San Francisco and Los Angeles. This project was expected to be completed in 2020 with a $33 billion budget, transporting Californian riders between the two major cities in a mere two hours and 40 minutes. The year is now 2023. Over the past 15 years, not one mile of track has been laid down, and price estimates currently sit at an astronomical estimated cost of $113 billion, with no concrete completion date in sight.

Though other nations have completed similar projects in the past with no serious snags—take, for instance, China’s high-speed rail, which laid down 25,000 kilometers of track within an 11-year stretch—California’s project largely differs in the sheer amount of lobbying by cities, businesses, and rail boards. Each group wants final say in the project’s vision; and yet, these conflicting voices have led to the construction process being greatly inefficient as a result.

This is most prevalent in the decision to lay tracks between Burbank and Palmdale, a 41-mile detour that would end up costing an extra $8 billion in expenses. Though building the entire track line along Highway 5 would’ve been a cheaper, more efficient solution, several members of the rail authority board have argued that the HSR would get far more passengers by passing through desert communities instead. Unfortunately, this detour created its own slew of issues, as passing along the east side would mean traveling through several residential zones.

After extensive pressure from previous CA Governor Jerry Brown, as well as Obama’s Secretary of Transportation, Ray LaHood, over 2000 parcels of land have been bought along this stretch, equating to several billion in expenses—a jump evidenced by the $2.8 billion increase from Madera to Bakersfield alone. This mass purchasing doesn’t only create issues in terms of expenses; those who have their homes and small businesses bought up suffer equally, as they are offered unjust rates with any attempts at refusing being liable to appeal from rail officials. As of now, land purchases account for 14% of the total budget, but this percentage is expected to increase as construction reaches the coast.

Unfortunately, lobbying is but one issue preventing this project from reaching completion; an even greater concern is the acquisition and spending of funds in the first place. While many voices have argued that the rail should begin construction around the endpoints, rail authority leaders ultimately decided to start construction in a stretch between Bakersfield and Merced. This move came after a grant from the Federal Railroad Administration, which provided $2.5 billion in funding under the stipulation that construction should start between Madera and Shafter, locations right in the middle of the Central Valley, with all funds needing to be spent by 2017. This decision has proved costly in multiple ways: not only was the rail authority pressured to issue construction contracts on land that wasn’t even purchased yet—leading to hundreds of millions of dollars in claims—but the location of initial construction has caused many onlookers to view the project with skepticism, coining the HSR a “train to nowhere.”

However, these concerns only paint a small portion of the great issue: while estimated costs were set at $105 billion at the start of 2022, this amount has since risen by another $8 billion, creating uncertainty over whether even more will have to be spent. Spending rates have continued to prove an issue as well, as although the rail authority claims to be accelerating construction, current spending sits at $1.8 million a day. Let’s put that into perspective: at current rates, the entire project would finish around the year of 2194.

Of course, this estimated completion time doesn’t take into account the rail authority’s issues in actually acquiring funding: Biden’s newest infrastructure bill would supply no more than $5 billion to the project, while any amount of state-level funding remains dubious at best. As CA Assemblymember Laura Friedman, chair of the Assembly Transportation Committee, stated, “This project is big and complex and complicated and difficult and needs oversight…It seems like there’s pressure being put on us to very quickly give them their money and just move on. ‘Legislature, get out of our way,’ which to me is really, really committing legislative malfeasance.” With lobbying, funding issues, and public doubt continuing to rack this project, it’s becoming increasingly unlikely that California’s HSR will get back on track—or see the light of day at all.