Making Every Vote Count

Could a completely different system of voting be the key to a better democracy?

October 18, 2022

Every election, many citizens fail to cast their ballots, a leading cause being distrust of the polling system. Currently, America follows the election system implemented by the 234-year-old Constitution: plurality voting. Due to the numerous flaws in this process, political analysts are in discussion of alternating the voting system which could better represent the majority and make each voter feel like their voice truly matters.

But first, what is wrong with our current system? Plurality voting is a “winner takes all” system where, to win, a candidate simply needs to receive more votes than any other candidate—not necessarily the majority (over 50% of the votes). In other words, a candidate that only gains the support of 40% of the population could win if no other opponent received as high of a count. Because “majority wins” is not guaranteed, most US citizens can dislike a candidate who still wins the election.

The consequence of a pluralistic system is the dominance of two major parties—Democrat and Republican—which renders every other candidate from outside parties insignificant. This leads to the ubiquitous phrase: “Don’t vote third party, you’re throwing your vote away.” The American people are left having to choose between the Democrat and Republican frontrunners they may disagree with because they don’t want to “waste” their votes. As a result, they either choose the “lesser of two evils” or don’t vote at all, and both outcomes end in disappointment. Because of plurality voting, US citizens are denied the freedom to express their nuanced opinions.

Plurality voting also perpetuates political divisiveness—the root of a crumbling democracy. Lee Drutman and Anne-Marie Slaughter of New America, a political think tank, wrote in a 2020 op-ed: “Under our current plurality rules, campaigns often play the ‘lesser of two evils’ game, filling the airwaves with negative campaigning that casts the opposing candidate and party as dangerous, extreme and radical, encouraging voters to fear and loathe the other party.”

There is a solution that tackles this issue at its root. Ranked-choice voting (RCV), also known as “instant-runoff voting,” allows voters to rank all their candidates in order of preference (first choice, second choice, and so on) as opposed to choosing one candidate.

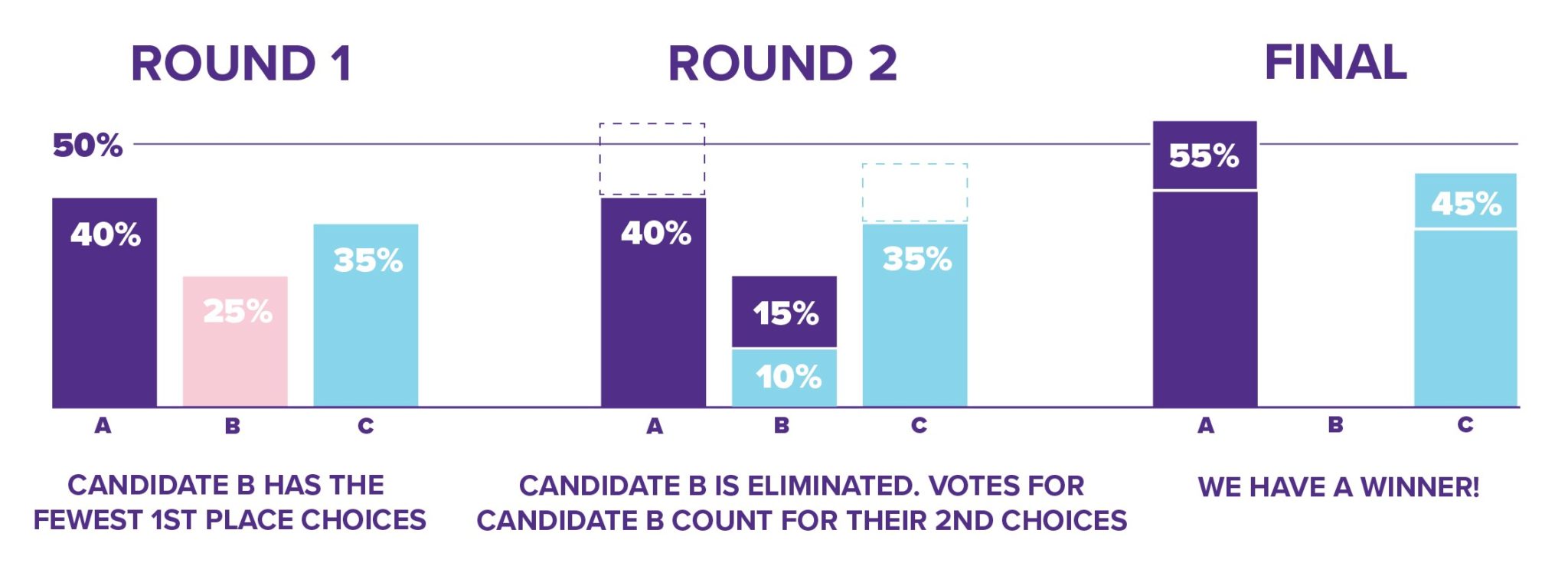

First, the first-choice votes are counted, and if anyone receives over 50%, they win. But what if no one has the majority? In a pluralistic system, the one with the most votes would win, but in a ranked-choice system, the candidate with the lowest first-choice votes gets eliminated, and the votes are tallied once more.

Everyone who voted for the eliminated candidate will have their second choice added to the rest of the totals. This system continues until one candidate receives over 50 percent of the votes and wins. See the model for a visual representation.

Now, none of the votes are “wasted” since their next choices are taken into account. A system like this is true majority rule and could be the key to breaking our rigid two-party system and electing a more representative government.

However, no system exists without its shortcomings—there’s a reason why ranked choice voting has only been implemented in a few states so far. The process of ranking candidates as opposed to selecting one is sometimes deemed “too complicated” for the general population and thus more susceptible to human error.

Moreover, opponents claim that a significant change in the voting process could potentially deter people from voting simply because of the inadaptability to change. In an age rampant with injustice, civil participation is increasingly important, so any chance of decreasing voter turnout seems too risky. However, data models from states that have already implemented RCV confirm that the risk of voter error and decreased participation is minimal: In Alaska’s 2022 Congressional Special Election, 85% of voters found RCV simple, and 99.8% of votes cast were valid. In Maine, the turnout of the first elections since starting RCV was actually higher than in previous elections without RCV.

When our current election system fails to represent the majority, re-evaluation is necessary, as America’s supposed foundations of democracy are undermined by the absence of true majority rule. A drastic change to a system that has been in place for centuries would inevitably prompt some pushback, but as partisan tensions are at an all-time high and public faith in the government falls to an all-time low, ranked-choice might just be the right choice.