Come Back to the Future

Literature surrounding doomsday tech is a whisper from the skittish past, and one we would all benefit from ignoring.

May 11, 2021

“Big Brother is watching.” That’s the underlying threat in George Orwell’s technodystopia 1984, wherein protagonist Winston Smith finds himself surrounded by oppressive technology designed to monitor and control the actions of the residents of the Republic of Oceania. Essentially, in a world surrounded by screens, there’s neither the possibility of respite nor time truly spent alone.

Orwell isn’t the first author to caution readers about the dangers of technology. The same trope of technological pessimism repeats itself over and over throughout literature: in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, Kurt Vonnegut’s Utopia 14 (or really any Kurt Vonnegut novel), and even in contemporary television like Futurama or Black Mirror.

So, are we really that much worse off for having grown up surrounded by broadcast news and Word documents, even when we consider all these cautionary tales? Time and time again, we see the same warnings: that technology will inevitably take our jobs, melt our minds, and entrench us deeply into the surveillance state. But what purpose do these “warnings” actually serve?

In the end, the media that demonizes technology is a work of nostalgia, not a legitimate cautionary tale. That’s because, to put it simply, digital technology is not optional anymore. The possibility of regressing to ten-cent soda pop and carrier pigeons has long passed.

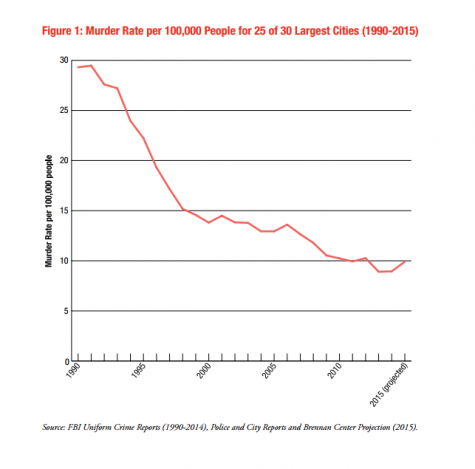

But even if we could get rid of technology, should we? Sure, we’re all pretty much glued to our cell phones, but I don’t think even Vonnegut could find a way to be mad about the concurrent decreasing murder rates since the 20th century. Actually, scratch that: he definitely could, but that doesn’t mean the rest of us should.

But even if we could get rid of technology, should we? Sure, we’re all pretty much glued to our cell phones, but I don’t think even Vonnegut could find a way to be mad about the concurrent decreasing murder rates since the 20th century. Actually, scratch that: he definitely could, but that doesn’t mean the rest of us should.

And less homicide isn’t tech’s only benefit: internet access means international communication at a click and widely accessible educational resources. It’s not just doom and gloom, which we too often forget. The tangible way that sensationalization divorces our conceptions of modernization from reality obscures both technology’s nuance as well as the true magnitude of its threat. Not only does our constant investment in these outdated dystopias prevent an accurate perception of the world around us, but it also forces us into a superlative pessimism that precludes what’s really important: the crucial examination and regulation of existing technologies. For instance, we could be passing laws to prevent AI bias if we weren’t busy huddling in a corner as machine learning develops unhindered.

Don’t get me wrong: our faulty views don’t stem entirely from Bradbury or Orwell. The onus is ours: both to interpret the continued relevance of novels from the 20th century and the extent to which we should be integrating them into our lives. We have already been irrevocably affected by the very technologies these novels deplore. Ask yourself: are you consuming this media with the goal of progressing forward, or simply clinging to the vestiges of the past? And if the answer is the latter, perhaps put down 1984 and enter 2021.