Vaccine Rollout Slower than Expected

This relief brought by the COVID-19 vaccine is unfortunately undercut by recent developments in the vaccine rollout scheme, where vaccine distribution is woefully behind schedule, largely due to the fact that the supply for the vaccine has not yet met the demand.

The extraordinary development of the COVID-19 vaccine has provided the American public with a momentary glimmer of hope amidst an increasingly worsening pandemic. This relief is unfortunately undercut by recent developments in the vaccine rollout scheme, where vaccine distribution is woefully behind schedule, largely due to the fact that the supply for the vaccine has not yet met the demand.

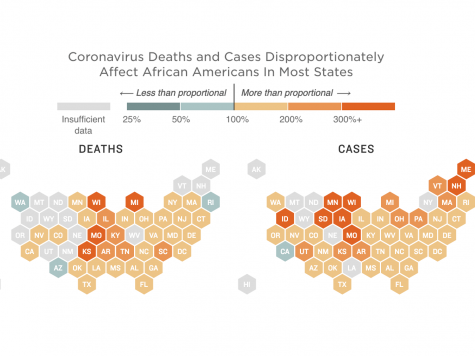

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has decided to ration the limited supply of vaccines for the next few months. At the moment, the CDC is factoring in inequities caused by systemic injustices in the healthcare system as part of their distribution efforts. Racial and ethnic minorities, in particular, have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, especially in terms of unemployment, illness, and death rates. In Chicago, for example, African Americans comprise 57% of COVID-19 deaths—a staggering figure that is due to the lack of adequate and affordable healthcare for those in the inner cities. To combat this, the CDC has allocated several thousand doses to these areas, in an attempt to mitigate the spread amongst those who must work in places where transmission is likely. Several doctors have pushed back against this strategy, suggesting that this strategy is not founded on a scientifically-proven method of mitigating deaths but rather on a political agenda.

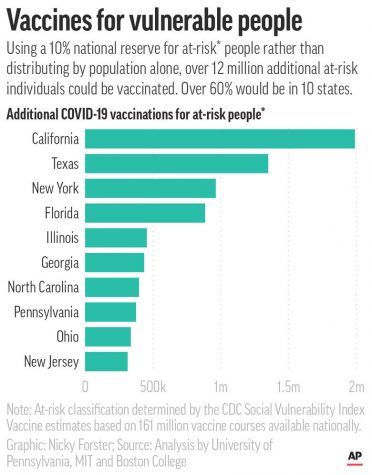

Although older-aged Americans are considered as a high-risk group, front-line workers are also greatly susceptible, as their jobs are critical in combatting the pandemic. For this reason, the CDC recommends that the vaccine be given to essential workers before the elderly, though they acknowledge that this decision will result in more deaths. This paradigm for vaccine distribution is also tied to the movement to ensure healthcare becomes more racially equitable. Harald Schmidt from the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics notes, “the older population is whiter. Society is structured in a way that enables them [white people] to live longer. Instead of giving additional health benefits to those who already had more of them, we can start to level the playing field a bit.” The White House, on the other hand, has a conflicting message, arguing instead that Americans over age 65 should be the first in line to receive the vaccine.

Several states, including California and Georgia, have chosen to adopt a vaccine rollout strategy that rides between these two ends of the spectrum, and they announced that they will be using an “equity metric” when distributing the vaccine. Some medical experts have aired their concerns with these strategies, which they view as politically motivated, asking instead: Why not simply distribute the limited vaccine based on the single metric of preventing the most deaths?

Distributing a scarce medical resource such as a vaccine is an imperfect art at best. Current plans combine science (who is at risk; for whom is the vaccine safe and effective; etc.) and ethics (justice, equality and equity) to decide who will get the first doses. Eventually, there will be enough doses for everyone who wants them, but until that time, these hard choices must be made. Crafting a COVID-19 vaccine distribution policy that not only acknowledges existing health and social inequities but also minimizes the loss of life is something that has yet to be accomplished by any country, as of this article’s publication.