Farmers Around the World Push for Change Amidst Pandemic

Farmers—both local and global—have been acutely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with supply chains being under heavy stress and farm workers becoming infected. In India, the situation for farmers has grown increasingly dire under new national legislation.

Farmers—both local and global—have been acutely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with supply chains being under heavy stress and farmworkers becoming infected. In India, the situation for farmers has grown increasingly dire under new national legislation.

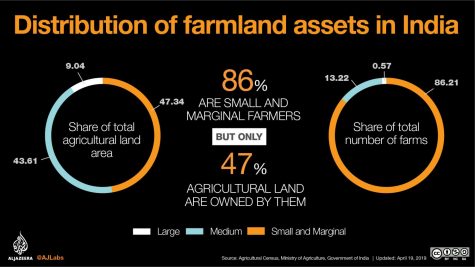

In September of 2020, the Indian government passed three new farming laws, all focused on deregulating the sale of crops from farmers to larger companies. This legislation has been fought by farmers across the country, who fear that big corporations may eventually force them off their land. The new laws let farmers sell directly to private companies, instead of the government acting as a middleman for sales. The government claims reforms are necessary to increase the efficiency of India’s farming sector, which accounts for over half of the country’s workforce but only about 16% of their gross domestic product (GDP).

By allowing farmers to sell directly to the companies, the government is no longer involved and the process moves faster than in the previous system. However in the previous system, farmers were guaranteed a minimum support price (MSP) by the government, so regardless of external factors such as natural disasters, economic policies, or political changes, they could always sell to the government and know what their profit would be. These new laws do not completely remove MSP, but get rid of many previous limitations on companies making deals with farmers. The deal-making process between farmers and companies will be free of many bureaucratic obstacles and government supervision that would normally protect farmers. This will likely lead to economic exploitation for the domestic farmers, many of whom lack the funds to hire legal representation to fight unfair contracts.

Many farmers also feel that their dissenting opinions aren’t accounted for in this new legislation. Modi’s government didn’t consult representatives for the farmers’ interests when making these decisions, instead looking to economists for counsel—whose “big picture” perspectives do not factor in the experiences of the farmers and the impacted population. “The government did not consult a single farmers’ organization” stated Yogendra Yadav, the president of Swaraj India, a political party that supports these farmers. While many of these economists agree that new laws are needed to increase efficiency, the way that the government has carried these out has been a topic of controversy. What farmers in India really want is for the MSP to be guaranteed for all, as in some places the MSP currently resides only on paper and not in the actual sales to the government—this would be further exploited with larger companies.

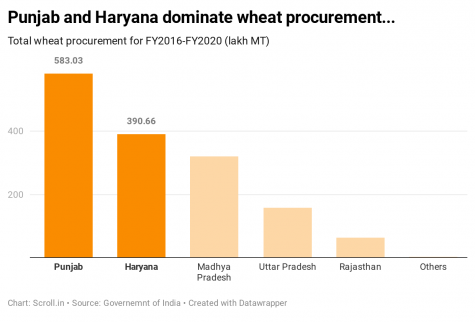

Protests of these laws started around September in the northern states of Punjab and Haryana, where the farming industry is an integral part of economic and socio-cultural spheres of life.

In November, the farmers marched to New Delhi, the capital, and in early December, protesters blocked highways around the city. These protests have yielded large returns for the farmers. Thanks to these individuals who have taken initiative and have used their right to protest, farmer unions now have access to government negotiations about laws that will have direct impacts on their lives, a welcome relief after many months of high tensions.

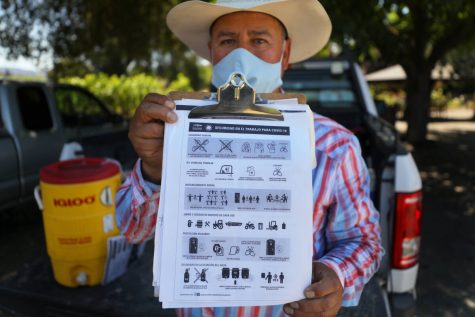

However, farmworker struggles do not only occur in India. With the onset of recent issues due to the virus, concurrent with prior struggles of modern farm working, farmworkers worldwide are facing various issues which in turn are affecting their mental well-being. As of now, farmworkers here in the USA are having their own share of struggles while they too endure the pandemic.

Prior to when regulations first took place, farmworkers already dealt with wearying work conditions while performing laborious tasks, including exposure to high temperatures, use of chemicals, and use of hazardous equipment. There is also the struggle of living with low incomes. While being financially challenged, having proper housing conditions and providing food becomes a struggle. Constant exposure to these conditions has been reported to be associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety. Farmworkers in the USA, many of whom are of Latino origin, face other compounding challenges of dealing with discrimination, living in a foreign country, and often worries of immigration status or family separation.

The need to support their families motivates many farmworkers, but when ends aren’t met, what once helped them persist through their laborious tasks brings down their spirits. As precautionary measures continue to take place, many families are struggling to adapt to new changes within their lifestyle. In response to school closings, families who work full time now must pay for childcare or quit their jobs in order to take care of young children. As many families report to be in debt, bringing food to the table becomes a challenge. For many farmworkers, this means to risk their own health and continue to work out in the fields. Ms. Fabian, a single mother of three, states, “We’re afraid of this illness. But we are more afraid that we won’t be able to make a living.” This fear then places farm workers in an unfortunate predicament: should they risk their livelihood or risk bringing back home the virus? Both options impose a great deal of stress and worry on farmworkers.

As previously mentioned, debt is one of the largest factors behind the worsening mental health struggles of farmers and has been exacerbated by the pandemic. For example, a family raising cows for milk in Wisconsin is making 40% less than usual this year and is facing $300,000 in debt, struggling to pay their bills and feed themselves. Small farms across the nation are facing similar hardships, though many of the reasons behind this debt also stem from long-standing issues such as severe weather, the trade war, and being replaced by corporate farming. According to The New York Times, more than 100,000 farms were lost from 2011 to 2018, with 12,000 of those being just from the last two years. Currently, farm debt is at its very highest: $416 billion dollars. Farmers have been losing money every year, often lowering the prices of their crops in an attempt to remain competitive and make whatever possible, though they usually end up getting less than it costs to produce them. Another American farmer says that he has been losing approximately $30,000 in a single month, and all of his family have been trying to find side jobs just to stay afloat—often in vain, because most rural areas have a weak economy and very few job opportunities.

Others have had no other option than stopping altogether. With the number of small farms continually diminishing, independent farming is starting to seem less and less a viable source of income, and many believe that this will speed up the decline of rural America. This is happening right now: the population is decreasing, businesses are moving, and over 4,000 school districts have closed, which in turn increases the difficulty of mere survival. While some have suggested a switch to organic farming, this is far too expensive for the farmers that are already deeply entrenched in debt with no government assistance, and little hope in the foreseeable future that this will change. Mary Riedmann comments, “I sometimes feel like they’re trying to wipe us off the map.”

Despite the appraisal that is given to essential workers, including farmworkers, there is still little action being taken to aid their families. With many in debt and out of work, farmworkers are struggling to provide for their families. As a student, you are able to help families in India by displaying your solidarity towards the Delhi protests and even donate to these trustworthy organizations: Save Indian Farmers, and Farmers’ Fund.

Additionally, from January 5th to January 29th, The Mitty Advocacy Project and the Latinx Student Union will be hosting a farmworker family drive, called Con Bondad, to provide relief and justice for farmworkers heavily impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. If you can help, we encourage you to click this link to order to provide much needed supplies and resources from an Amazon Wishlist, which will then be delivered to the Center for Farmworker Families. Please click here for more information about the drive.

As more issues continue to arise and be amplified by this pandemic, it is important to take action and to be vocal advocates for change.