Then and Now: The Marginalization of Indigenous Peoples

For centuries, indigenous people have been wrongfully displaced and decimated by European encroachment, disease, and forced assimilation. The atrocities of colonization and genocide have uprooted indigenous civilizations, leaving lasting impressions on today’s native peoples.

November 11, 2020

For centuries, indigenous people have been wrongfully displaced and decimated by European encroachment, disease, and forced assimilation. The atrocities of colonization and genocide have uprooted indigenous civilizations, leaving lasting impressions on today’s native peoples.

Then: Historic Injustices against Indigenous Peoples

From a young age, children are taught romanticized versions of American colonial exploits. The most well-known story of Thanksgiving, revolving around the peaceful, friendly meeting between the Wampanoag tribe and the English colonists, is one explicit example of the injustice done to indigenous history in American education. This interpretation of events is glaringly false, as it portrays the settlers as heroic saviors, while ignoring the deadly conflicts and horrific abuses that were committed against the indigenous peoples. History textbooks rarely mention the Pequot massacres of 1637, nor is there any acknowledgement of the robbing of Wampanoag graves. Hundreds upon thousands of indigenous folk were wronged, yet their murderers are celebrated today through the declaration of Thanksgiving as a national holiday. In all truth, Thanksgiving is more a celebration of the massacres against the indigenous than it is a commemoration of peace and harmony.

In the 1700s, the arrival of Spanish missionaries posed another major threat to indigenous culture and way of life. These Spanish missions were established along the coast of California, from Sonoma all the way down to San Diego. Despite the glorification of these missions in elementary school curriculum projects, these missions ultimately involved some of the most atrocious and darkest aspects of American expansion into the West. As part of the encomienda system, the native people of California were forced into cultural and religious assimilation, as well as inhumane labor conditions. Colonists regarded the natives as ‘property of the church,’ destroying their culture and replacing it with their own as part of organized assimilation programs.

The Destruction and Erasure of Indigenous History

This injustice against indigenous peoples was then hidden through a process called selective reconstruction. Mission administrators’ restoration efforts in the name of historical conservation were, in actuality, attempts to paint an inaccurate narrative of native experiences on these sites—preserving aspects of the mission system that aligned with self-interests and values. Soldier’s quarters, monjerios (locked concubine chambers), and whipping posts, where native peoples were brutally assaulted and confined, were rebuilt in such a way that glossed over these horrific struggles. During the restoration of Mission Soledad, for example, local residents desecrated the mission’s original indigenous cemetery and turned it into a parking lot for tourists. “[In doing so], they removed the visual evidence of the mission’s most important effect upon Indian life: death.” Other visual evidence of brutality was obscured and replaced by greenwashing; large fields and courtyards were replaced with historically-inaccurate gardens, in which tools used by enslaved natives were repurposed as garden decor. This erasure of native history has given the American education system an excuse to color what was (and arguably still is) a story of persecution and devastation as a rosy narrative of cooperation and friendship.

Now: Local Tribal Lands under Siege

These historical injustices suffered by the indigenous people of California have translated into modern forms of discriminatory practices. The land ownership rights of indigenous communities, for example, are constantly violated by government and corporate interests, which seek to financially profit off of the valuable natural resources found on native land.

In fact, this is occurring locally on Juristac (Huris-tak), the ancestral lands of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band in Gilroy, California. Today’s Amah Mutsun Tribal Band are survivors of the destructive reign of Mission San Juan Bautista and Mission Santa Cruz. Also known as the “place of the Big Head,” Juristac is a sacred site where tribal traditional healing and renewal ceremonies take place. It is also one of the last remaining undisturbed areas belonging to the Mutsun people, as most surrounding ceremonial sites and places of gathering have already been lost to industrial development.

Today, however, Juristac is in danger.

A few years ago, an investor group “purchased” the land, looking to develop a sand and gravel mining operation for construction purposes. The operation, named Sargent Quarry, would essentially clear nearly 320 acres of sacred land. The property owner and land planners hope to—and likely will—reap tremendous financial benefits. However, these monetary benefits come at the cost of the spiritual well-being of the Mutsun people, who, for centuries, have valued their homeland as a place of great natural and cultural significance.

Animism in Native American cultures are highly spiritual and involve many rituals, like those of coming-of-age. Various communal ceremonies are performed to cleanse the soul, to heal after the death of a tribe member, or to celebrate the birth of a new baby. Many Native American tribes value their spiritual connection with their ancestors, seeking wisdom and guidance from them. Native American culture is also interconnected with their natural surroundings.

Native Americans find spiritual value in connecting with plants, animals, mountains, trees, fire, air, earth, and water; for example, it is customary to thank the animal for their life which provides their food, or the Earth which provides fertile soil to cultivate crops. Once the land is disturbed by mining, however, there will be no way to restore the cultural and spiritual features of the landscape. The chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, Valentin Lopez, adds, “without these spiritual sites, we lose our purpose for being here.”

Protect Juristac is a community cause led by Amah Mutsun Tribal Band in saying NO to sand and gravel mining at Juristac. You can learn more about the updates on this issue here.

Compounding Crises: The Native Response to the Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has also laid bare the deep inequalities created by the colonization of indigenous peoples.

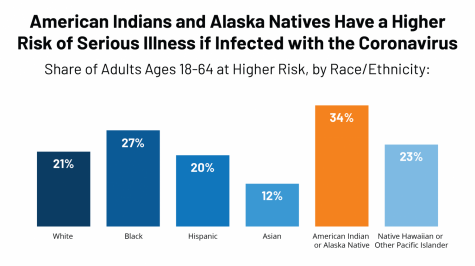

But how are they really being affected? Many indigenous families come from low-income households, often working in low wage “service” occupations—often essential services— that require them to work vulnerably outside the home. This forces many indigenous workers to come into contact with potential carriers of the virus, and work in environments that simply cannot follow proper social distancing protocols. In addition, many families lack access to modern technology and safety measures that have resolved many of the issues experienced by non-indigenous families throughout quarantine. A report by the Center of Disease Control (CDC) corroborates this finding: COVID-19 is detected 3.5 times more in indigenous people than to white people.

Many also have a high mortality risk to the disease due to common pre-existing conditions, mainly because many indigenous communities are located in food deserts, where healthier food options are often scarce, leading to an onset of conditions such as diabetes, kidney disease, and heart disease due to an unhealthy diet. While it is important to note that indigenous persons did willfully bring these physiological conditions upon themselves through dietary habit choices, it is more important to note that it is the failings of our leaders who refuse to recognize, address, and fix these issues that are ultimately the cause of this continued devastation.

How can you help?

Although the current situation may seem bleak, now is not the time to turn a blind eye. We have an opportunity now to correct the course of American treatment of indigenous peoples. Donate to programs and charities that are working towards the community. Join others in rallies and protests against injustices against indigenous communities, both locally and globally. Although many students cannot show support in these ways, there are other ways to make changes in your behaviors and attitudes toward native peoples. Dismantle the stereotypes of indigenous persons and the cultural barriers that separate us. Be open to accept and learn about different cultures. And most importantly, stay educated on local indigenous communities and the many injustices they may face. Together, we can combat the silence and ignorance that slow change.