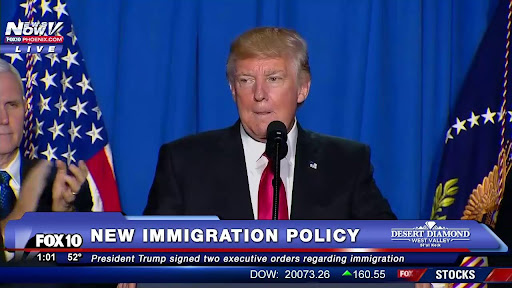

The first Trump administration’s immigration policy had a significant impact on immigrant and international students and their families. For immigrant students, administrative actions targeted undocumented students through the rescinding of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), denying loans, and expanding immigration enforcement. For international students, the most impactful administrative policy was the travel ban, also known as the “Muslim ban,” scrutinizing certain visa applications to limit travelers coming from certain countries. There were also attempts to limit Optional Practical Training (OPT) and Curricular Practical Training (CPT) programs, which were commonly used by international students to get work experience during or after their study in the U.S.

The second Trump administration’s immigration policy is expected to have an equally large impact on the student body. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there are more than 45.3 million immigrants residing in the U.S., making up 13.7% of the nation’s population, according to this article. This percentage climbs when considering only the students of immigrant origin. Since 2022, 5.8 million students from immigrant families have constituted 32% of the student population enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities, leaving them vulnerable to administrative policy changes.

As for international students, they accounted for more than 1.1 million in 2024, which was more than 6% of the total U.S. higher-education population. At Stanford, the total percentage of international students in 2022, both undergraduate and graduate, rose to 24%, or 4,195 out of 17,326 total enrolled students, which was significantly higher than the average percentage of the international student population. But the percentage further increases to 34% if only graduate international students are considered.

It is not only the administrative policy change that has a material effect. The uncertainties surrounding a potential policy change can have a significant impact on how international students make future choices, including where to study, where to work, and where to live. The reduction in the talent pool may negatively affect the economic engine that we all rely on. Stanford economist Ran Abramitzky, a professor at the Department of Economics in the School of Humanities and Sciences, often speaks about the grim prospect of limiting immigration.

In Abramitsky’s 2020 interview, he discussed the restrictive immigration policy’s impact on the creativity and competitiveness of businesses, which heavily rely on what the new graduates bring to the industry. He pointed out what happened when the U.S. closed its borders to immigrants in the 1920s as a history lesson–instead of paying American workers better wages, industries that couldn’t attract new workers at lower wages shrunk and others turned to automation. None of them benefited the workers.

Today, the industry is already saturated with automation technology, and they are likely to look at outsourcing, remote work across international borders, or artificial intelligence (AI) as solutions instead. Ironically, outsourcing, remote work, and AI heavily rely on foreign or international workforces for them to function. Unfortunately, American industries and workers are unlikely to benefit from the restrictive immigration policies this time either, and it may further deteriorate the prospects for international students, pushing the economy into a downward spiral.