Two things are certain in life: death, and long lines. But while lines might be only a hindrance and a test of patience to some, in other situations, they can be a matter of life or death. And no line is more critical than the waiting list for organ transplants.

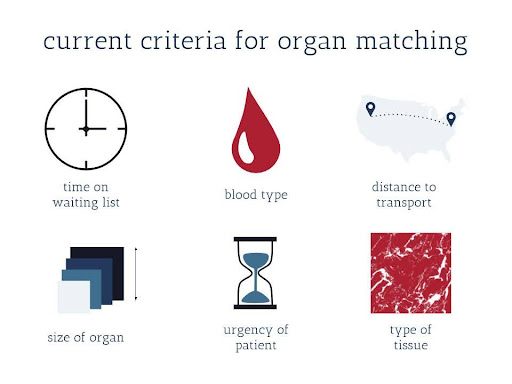

The US organ transplant system is managed by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), which is made up of many smaller Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs). Their work ranges from recovering organs from deceased donors to facilitating the donation process. However, this organization has little say in who gets the organs themselves. Instead, a computerized system is used to match donor organs with suitable recipients. This complicated process requires many considerations, with computer algorithms generating a ranked list of potential recipients for each organ. Factors like compatible blood and tissue types, organ size, urgency of need, and waiting time are all evaluated in the search for the organ’s recipient.

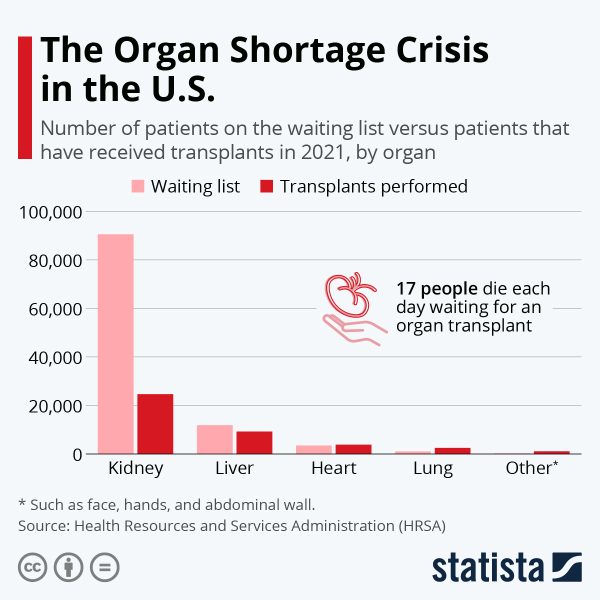

Currently, over 100,000 individuals are on the waiting list for an organ, with a new addition added every nine minutes. But every two hours, someone on the transplant waitlist dies waiting for an organ that didn’t come fast enough to save their life. Furthermore, according to a New York Times investigation, hundreds of patients are being skipped over on the waiting list, with the organs going to people in less precarious situations instead. This activity goes against the system’s basic foundation that outlines how patients in urgent need of organs who match the donor’s organ must be prioritized. The New York Times investigation also found that in 2024, for almost 20% of the organ transplants that occurred, patients on the waiting lists were skipped over, forced to compromise their health for others who either had not been on the list as long or simply were not as sick. As a result, despite nearing the top of the waiting list, over a thousand people lost their lives without learning whether the organs they were deprived of could have saved them.

This dire inequality is not just an issue of numbers—organ transplant inequality affects individual human lives, no matter the age of the individual. Senators Chuck Grassley from Iowa and Ron Wyden from Oregon have called out line skipping in the business of organ transplants, specifically citing Marcus Edward-Parr, a 15-year-old from Michigan. Facing severe medical conditions for almost his whole life, Marcus had been waiting for a kidney match for almost 10 years. When given an opportunity for the “perfect” match, he finally had hope of improving his health condition. Yet, rather than following the waiting list, his name was passed off, leaving him with a less fitting kidney, leaving him vulnerable to complications and potentially needing another transplant in years to come.

This dire inequality is not just an issue of numbers—organ transplant inequality affects individual human lives, no matter the age of the individual. Senators Chuck Grassley from Iowa and Ron Wyden from Oregon have called out line skipping in the business of organ transplants, specifically citing Marcus Edward-Parr, a 15-year-old from Michigan. Facing severe medical conditions for almost his whole life, Marcus had been waiting for a kidney match for almost 10 years. When given an opportunity for the “perfect” match, he finally had hope of improving his health condition. Yet, rather than following the waiting list, his name was passed off, leaving him with a less fitting kidney, leaving him vulnerable to complications and potentially needing another transplant in years to come.

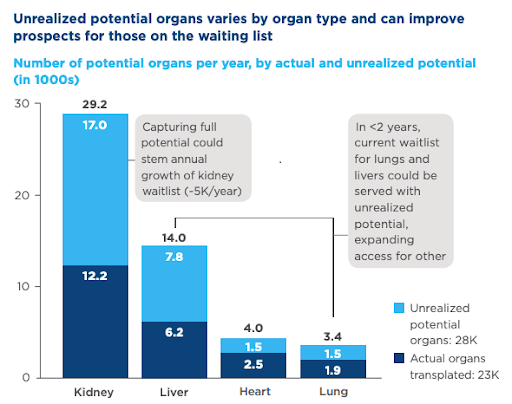

The obvious solution to long waitlists is more donors. But that isn’t exactly the problem the U.S. is facing. Currently, over 170 million individuals are registered organ donors. However, only 1% of these people actually donate their organs upon dying. This is often due to the specific set medical requirements that need to be met in order for an organ donation to take place. Still, each year, over 28,000 eligible, donated organs aren’t reaching patients. For many, an organ transplant is a lifeline, but each year, tens of thousands of patients are being denied another chance at life with their replacement organs going to complete waste. All of this is because of systemic inefficiencies, with a lot of mismanagement occurring within the Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs). Dr. Malay Shah, surgical director of the liver transplant program at the University of Kentucky, states, “It feels like some OPOs don’t see organ donation as their primary mission.”

Indeed, cases of fraud and abuse have been well documented with many OPO organizations. The money these nonprofits receive is from the federal government; however, the costs simply don’t add up. Hundreds of thousands of dollars have disappeared in the last fiscal year. This money was given to these organizations to help the most vulnerable. But instead, much of it has been used to line the pockets of opportunistic workers, who have fraudulently used the money for their own needs rather than for additional organ transplants.

Although the situation is dire for patients on organ transplant waiting lists, there are solutions. Providers of dialysis and other providers for patients with organ failure can create pathways to more directly refer patients to transplant centers. Transplant centers and organ procurement organizations can implement training to improve their approaches to evaluating and choosing patients.

Additionally, those benefiting from transplant inequality should be held accountable for harms that they cause to patients and stakeholders can be incentivized to fight against inequality. These reforms offer a new light in this plight that has distressed thousands of people. With them, we can cut down lines, not lives.