From tamagotchi pets and Beanie babies to Nickelodeon and the rise of the World Wide Web, the 90s were truly memorable–even for the group of chemists working in the UC Berkeley lab, who were on a winning streak after creating 13 completely new elements in the race to grow the periodic table. And they were eager to continue it.

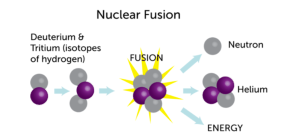

The process they used to make elements, called nuclear fusion, was essentially smashing two smaller atoms to create one larger atom–hopefully–of an undiscovered element. Atoms are determined by how many protons they have in the nucleus; no matter how many electrons or neutrons an atom with 1 proton has, it will always be hydrogen. So, if you smashed one hydrogen with another, you’d get an atom with 2 protons: helium.

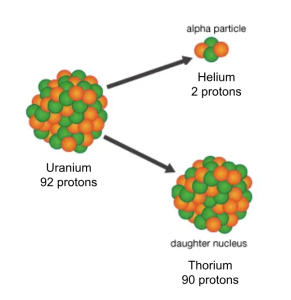

By 1999, the biggest element had 112 protons. Theoretically, if you could smash krypton (86 protons) and lead (208 protons) together, then you’d have the element with 118 protons. Then you could carefully strip off 2 protons at a time (as helium) to discover the elements with 116 and 114 protons–a process using alpha decay chains.

This is exactly what the Berkeley lab was trying to do, and what better scientist to take this challenge on than Victor Ninov, who had participated in the creation of elements 110, 111, and 112 using his very own program, GOOSY, which analyzed alpha decay chains. So when the rest of the Berkeley team was away on vacation, Ninov set to work by himself in the laboratory.

Very soon, almost a little too soon, he discovered traces of element 118, meaning he had also discovered 116 and 114 from alpha decay chains. It was a groundbreaking discovery. The Berkeley team hurriedly published these findings, ecstatic to regain their streak.

Yet, in German and Japanese labs, Ninov’s results could not be reproduced. Suspicion was mounting, and it wasn’t long before it was found that Ninov had faked his findings, manually changing data in the GOOSY program to make it seem like the perfect decay chain was observed.

The scandal, which was highly reported on, completely destroyed his reputation and served as a warning against manipulating data. Just a few months ago, Harvard was almost sued for over $25 million for data manipulation and fabrication in four research papers authored by their professor Francesca Gino, who ironically studies dishonesty.

The scandal started with a paper published by Gino in 2012, titled “Signing at the Beginning Makes Ethics Salient and Decreases Dishonest Self-Reports in Comparison to Signing at the End”; it was retracted in 2021 after it was revealed that the data reported just didn’t add up. With further investigation, a co-author on the paper from Duke University revealed that he had mistakenly “mislabeled” the data, but did not report anything about fabrication of data.

However, it was later found that there were high chances of fabrication by Gino, who was in charge of the data collection and reporting. With this new information, Harvard had called for the retraction of three more of Gino’s papers and ongoing allegations continued to be investigated. It was recently reported that the lawsuit for these allegations was dropped, but Gino still suffered a tragic hit to her reputation as a researcher.

Science is an ever-changing field, and results must always be reproduced to become more widely accepted. If there are any issues with documentation, deliberate or not, the validity and authenticity of true science is put at risk.