On February 14, 2024, Regional Medical Center (RMC) of San Jose announced it will be closing its trauma center service by August 12 of this year, in which patients—inflicted with severe injuries from a traumatic event (e.g. car accident, major falls, gunshots, etc.)—will soon be turned away from Regional Hospital and transported to other local hospitals. The hospital’s STEMI (ST-Elevation- M.I) program, a procedure in which patients facing active heart attacks are rushed to the cath lab for further treatment, is to follow suit and close alongside the trauma center.

Why close? Regional Medical Center spokesman Carmella Gutierrez cites the rationale behind the decision is to focus its medical efforts and budget of $10 million into improving care in the Emergency Department and increase patient capacity from 43 beds to 63 beds. The hospital also claims that the trauma center has seen a decline in severe cases over the past several years, so its resources are better off distributed to other departments.

In San Jose, Santa Clara Valley Medical Center and Stanford Hospital are the closest trauma centers relative to RMC, of which—in distance metrics—are respectively 8 miles and 27 miles away from Regional Hospital. With a municipal population of around 1 million people, heavy and unpredictable traffic within San Jose makes it so that commuting 8 miles or 27 miles to be a headache in it of itself, but for patients who have to travel such distance to receive treatment, it is direly displacing them onto the brink of life-or-death.

In response to the announcement, UC San Francisco Dr. Renee Hsia shares her sentiments and dissects the research that she conducted. In what she deems the “golden hour”—the first hour in trauma care—she measured the change in mortality rates of injured patients before and after the closure of a local trauma center and found that “when you had a trauma center closure and had to be driven further, your mortality increased by 21%.”

Santa Clara Valley Medical Center (SCVMC) and privately-owned Stanford Hospital are both rated as Level I Trauma Centers (rated higher than that of RMC), and thus may seem to promise better outcomes and better methods of recovery for highly-injured trauma patients.

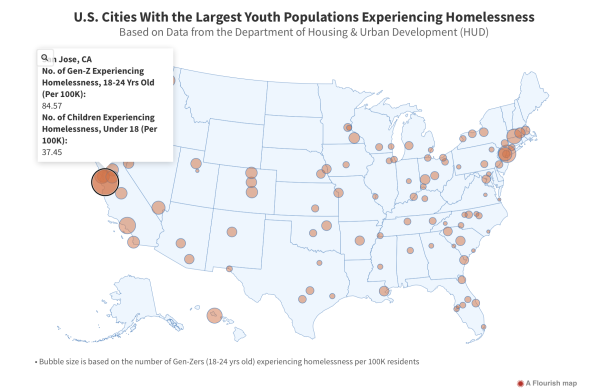

Yet, these better-funded medical centers are erected in higher-income areas—i.e. Campbell and Palo Alto respectively. On the flipside, Regional Medical Center is located at the borderline of Silver Creek and Alum Rock, cited as lower income neighborhoods of San Jose—which, as its own entity, is now deemed the city with the highest rate of homeless youth per capita in the nation.

Melissa Gong, a nurse working for Regional Medical Center, states she found out, via email, about the news a day before it was announced to the press and comments that “the patient population that we serve at Regional… caters to a certain population in East San Jose. These are patients with low literacy rates, low access to care and difficulty trusting healthcare professionals.”

As such, the closure of the trauma center has the potential to disproportionately affect patients of these lower-income areas of San Jose and further inflict the plight of medical inaccessibility onto these patients who might not be able to afford the medical costs at the more expensive hospitals. Currently, both SCVMC and Stanford also do not have the resource nor staff capacity to be able to provide these transferred patients from East Side San Jose with adequate levels of care, for the volume of trauma patients is currently about the same at all three hospitals (the closure of the RMC trauma center can entail the population of trauma patients to double in size at either of the two other trauma centers).

Surprised about the sudden announcement, San Jose Mayor Matt Mahan also adds to the criticism saying, “We don’t ever wanna see life-saving medical services cut, particularly in our lower income neighborhoods. The fact that east side San Jose will have to travel farther to get a trauma center is concerning.”

As someone who had not only volunteered at RMC for over a year and a half but was also born at RMC (a reality no longer possible because the maternity ward had also closed in 2020 because of budget cuts), I recognize the value in prioritizing the Emergency Department: patients at RMC often have to wait hours before treatment sheerly because of the lack of funding and human resources.

Yet, my personal interactions with the charitable care that RMC has for its homeless population (e.g. clothing homeless patients with clothes from the closet dedicated for the homeless) makes me frightened for the near future in which many of these patients will be turned away or not treated with the same level of care that they were treated with at RMC.

Furthermore, in 2020, my grandpa was admitted to the STEMI program at RMC because of a stage III heart failure, and because of his close living proximity to RMC, he was able to receive the appropriate treatment and is now still thriving four years later. I can’t even fathom the harsh reality that many families will have to bear after August 12 in which they’ve lost a loved one because of long commute times to other trauma centers in San Jose.

So, what can we do? Figures such as Dr. Varun Kapur, trauma surgeon and ICU physician at RMC, have taken it to the media to publicly critique RMC’s decision and are pressuring the Santa Clara County to intervene and appeal the closure.

Likewise, San Jose Councilmember Peter Ortiz—who sentimentally cherishes RMC’s trauma center because his mother had been admitted and treated at RMC for a sudden heart attack just this year—has announced his commitment to working alongside RMC to negotiate the closure. As such, we can only hope for an appeal in RMC’s decision, and supporting policy makers like Ortiz is our best bet in protecting the lives of our loved ones and our local community.