Dada: Crazy Art for Crazy Times

October 1, 2020

You might have looked at the title and asked yourself, “What is Dada, and how does something that sounds like a baby’s first words relate to today?” Well, my dear reader, let us first go to Zurich, Germany in August 1914, a city reeling from the beginning of the Great War, a conflict of destruction and horror. Many saw the outbreak of the war as a result of capitalist and colonialist “logic” and decided to use a contrastingly nonsensical movement to protest against the intellectual and cultural homogeneity that corresponded with the war.

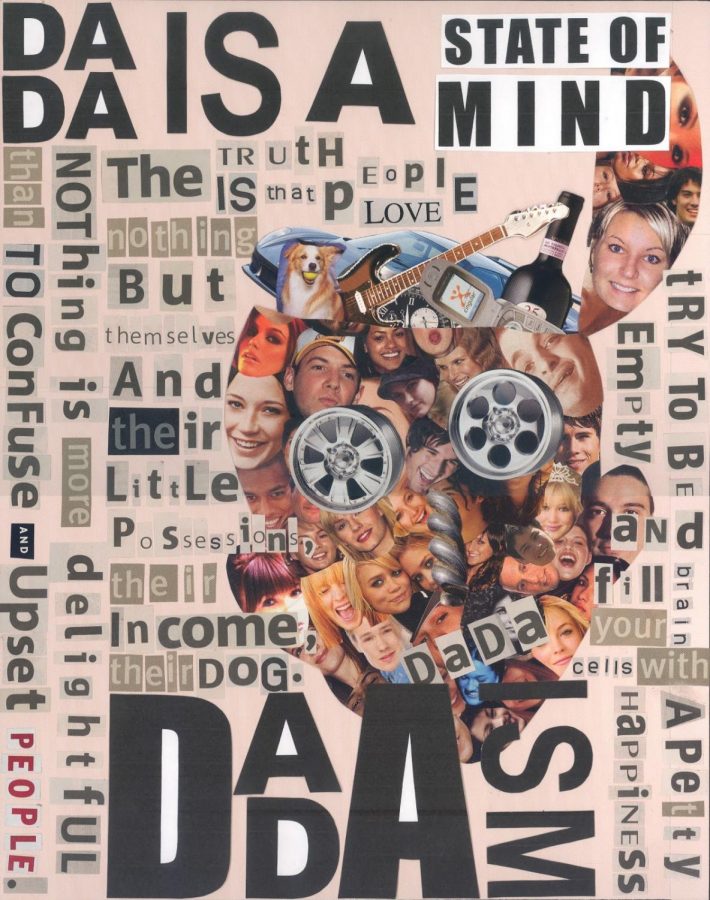

Dada thus emerged as an artistic expression that embraced chaos and irrationality, designed to protest against (in George Grosz’s words) “this world of mutual destruction.” As Hans Richter described, it is “anti-art”; traditionally, art was meant to be aesthetically pleasing, but Dadaism ignored that, seeking to offend rather than appeal to sensibilities. The origin of the movement’s name is also debated, with theories from it being randomly picked from a French dictionary, to repetitions of “Da” (which is “yes” in Romanian), to it just being plain nonsense.

Dada came into form alongside similar modernist movements like Futurism and Expressionism, but there was one key difference: Dada incited such shock and scandal that Dadaist magazines were banned and some artists were even imprisoned. Dadaist art was mostly visual and literary, with its poetry breaking all the normal rules and discussing subjects like nihilism and paradox to create a nonsensical, chaotic piece.

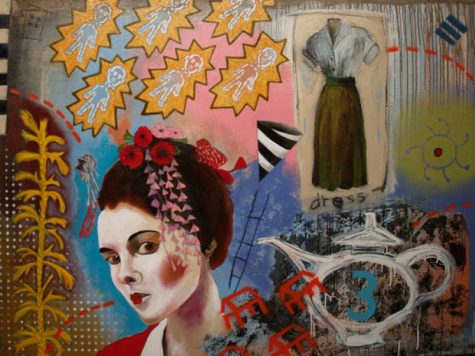

The visual art used techniques such as collage (a cut-up technique to make poems from disordered newspapers), photomontage (which used printed photos instead of newspapers), assemblages (which were 3-D versions of collages), and readymades, a technique used by Marcel Duchamp in which he would add a short, unrelated sentence to a physical piece, provoking thought in a way that may not be evident at first.

Dada is still relevant today, as there is so much insistence today on following the career track of succeeding in school, going to college, getting a high-paying job, and buying a house, just like everyone else. In addition to this idea of the “optimal career track”, there’s an idea that one’s gender has very specific activities and appearances linked to it (such as men doing more physical labor or women wearing form-fitting clothing) and that one must be male or female and must love someone of the opposite gender: in a word, heteronormativity.

So the conformity that Dada hoped to protest against is still often being emphasized today, and those who deviate from this path are sometimes even shunned, just as Dada’s differences with common art led to people attempting to erase its effect. Those who drop out of college or never go to begin with are spoken of as cautionary tales of what not to do, even though many of these people are successful in their own right.

As Dadaists noted in the Great War, homogeneity in thought and society can lead to disaster. They protested against this with their stunningly chaotic art; similarly, we should not let a singular perspective become the dominating societal norm. No one needs to go to the extremes of Dadaists in their art, but by emulating the concept of being unapologetically different in our lives, we can make the world a more interesting place — a world where multiple viewpoints and perspectives replace singular truths and people of differing beliefs are able to respect each other instead of regard others with suspicion.